Friends, the final version of this article was published at: http://www.learnnc.org/Index.nsf/doc/comics0703?OpenDocument. This version is still missing a wee bit of content.

>>Another draft of this article. Some images missing. Again, if you have meaningful comments, do it up.

Comics in the Classroom

Comic books. You’re probably thinking about Superman or Spider-Man. Batman

or Wonder Woman. Maybe cheap, cheesy horror stories, pirate adventures, or some

other muscle-bound, spandex-clad crusader whose first response is a strong punch.

You’re probably not thinking about your classroom right now.

You should be.

Comics in Culture

A recent explosion in academic interest in comic books and graphic novels has

stirred the creation of comics curricula nationwide. Several colleges and universities

are now offering courses in comics literature, and high school teachers are

exploring graphic novels as a new way to stimulate young readers’ interest in

literature. The National Association

of Comics Art Educators is producing exercises,

study guides, and handouts on comics in the classroom, and several comic

book companies, notably CrossGen, are

including resources for educators in each issue they produce. Comics have been

the subject of a national best-seller, Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures

of Kavalier and Clay, and novelists and screenwriters like Brad Meltzer and

Kevin Smith have lined up to write the adventures of the heroes they grew up

with. Art Spiegelman’s Maus, the story of his father’s internment in Nazi Germany,

was the first comic to win a Pulitzer Prize, and comics have nabbed prestigious

awards in other fields.

Considering the success of comics-inspired film and television shows like Smallville,

X-Men, and Hulk, and their popularity with children, there is a tremendous interest

in comics-related material that educators could easily turn into an enthusiasm

for reading. However, it’s difficult to know which comics are appropriate for

children, and many educators place a stigma on comic books– a stigma that dates

back to the 1950’s, when at the height of McCarthyism, comics were the targets

of congressional scrutiny. (For an abbreviated history of comics, check A

Brief History of the Comics Universe.) In fact, it’s tough to know what

a comic is, when the most respected example of the form, Maus, received this

“praise” in the New York Times: “Maus is not a comic book.”

What Are Comics?

Comic books, the pulpy-papered, saddle-stapled mixture of art and story, have

gained a new respect from the literary community in the past fifteen years.

The alter ego of the comic book is the graphic novel, which is also a medium

in which stories are told through both text and pictures, but replaces the flimsy

saddle-stapling with solid binding. Increasingly, comics publishers are collecting

multiple issues into single volumes, and comics writers are responding with

more ambitious and artistic story arcs that spread across many issues. Graphic

novels are increasingly appearing in local libraries, are reviewed alongside

traditional novels in publications like the New York Times and Entertainment

Weekly, and have sections devoted to them in bookstores and on Amazon.com.

With a renewed emphasis on independent reading in schools, comics appeal to

students and teachers with a variety of interests and are increasingly being

seen during D.E.A.R. (Drop Everything and Read) time. Comics have a wide range

of subjects, well beyond the super-hero or funny animal. Because they are cheaper

to produce now than ever before, the comics industry is now able to take gambles

on more artistic fare that’s been less traditionally marketable than super-hero

comics. Until the 1980’s, comics appeared on newsstands, and up to 50% of comics

might be returned to the publisher if they didn’t sell, which meant tremendous

pressure to create the “next big hit.” Most comics are now distributed through

speciality retailers and mass merchants, which means unsold issues won’t be

returned, and small companies have more freedom to explore offbeat writers and

artists.

As a medium, comics and graphic novels (which are lumped together in a term–

“sequential art”– coined by one of the field’s pioneers, Spirit author Will

Eisner), now have a definitive textbook, as well. Scott

McCloud penned Understanding Comics, which explored the medium and its history

in comic form. His sequel, Reinventing Comics, is also penned as a comic book,

and explores the effects of new technologies and cultural changes on an existing

industry.

McCloud defines comics as "juxtaposed pictoral and other images in deliberate

sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response

in the viewer." According to his definition, the following set of images

would be a comic:

However, as teachers, we know that this image more than likely belongs to an

instruction manual. We expect comics to look something like this:

Each of the images serves the same purpose, in the end. The reader is expected

to see a progression of time through images displayed in a certain order. Looking

at the two examples, we can deduce that comics may be strong teaching tools

for visual literacy, and McCloud supports this by analyzing the six types of

transitions in comics, and how their use is fairly consistent among artists

who seek to convey meaning with images.

But Are Comics Appropriate For the Classroom?

The short answer: some are, some aren’t.

StoryArk provides a list

of how comics can fit Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences, and James Sturm,

author of the acclaimed The Golem’s Mighty Swing, makes The

Case for Comics. Read-Write-Think provides a lesson plan for using comics

as an introduction to narrative structure.

Comic books and graphic novels have a wide range of styles and subject matter.

They range from social commentary to fantasy to autobiography to mystery to

didactic. But, as with any reading in the classroom, teachers should consider

their classroom objectives, the age-appropriateness of the materials, and MELISSA,

ANY SUGGESTIONS?

If you’re a teacher or media specialist, and you’d like to try using comics

in your curriculum, here are some suggestions. You can find more at No

Flying, No Tights, a website devoted to reviewing graphic novels for teens

and kids.

|

Maus Relevant subjects: Art, Language Arts, Social Studies Perhaps the best-known comic in the world, Maus tells the story of Spiegelman’s |

|

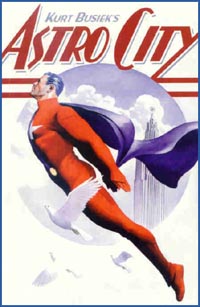

Kurt Busiek’s Astro City: Life in Cig City Relevant subjects: Art, Language Arts, Psychology, Social Studies What do super-heroes dream about at night? How do they go out on a date? |

|

Orbiter Relevant subjects: Art, Language Arts, Psychology, Science, Social Studies Life is different for Americans since the space shuttle Orbiter disappeared |

|

Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood Relevant subjects: Art, Language Arts, Social Studies Best used with high school students, Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood |